Summary

• Implementation/designation of MCZs should be evidence-based.

• There is very little evidence that MCZs work in temperate sediment dominated areas for fisheries management or biodiversity.

• It is not clear what the purpose of the proposed MCZs in temperate sediment areas are and how they will impact on the fishing industry or biodiversity.

• There is a need for better consideration of co-location possibilities.

• Lack of certainty leads to heavy discounting of the future by fishermen and ineffective management/poor cooperation.

• Time should be taken to get our coastal marine management strategy right rather than implementing broad-scale and ineffective measures based on gut-feeling.

Fishery exclusion zones off the yorkshire coast

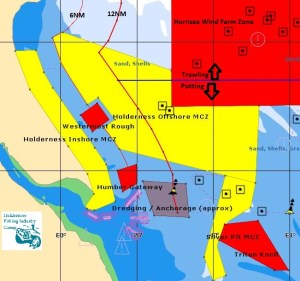

Figure 1: Activities in the Holderness Coast area (From Bridlington to south of Spurn Point). Red areas a current and planned windfarms. Yellow areas represent three of the proposed MCZs in the region. Blue areas represent those left over that fishermen would be able to fish if MCZs evolved to become no take zones. The blue line represents the voluntary separation between trawlers and potters. Prepared by Mike Cohen, CEO, Holderness Fishing Industry Group.

About the author

I am a lecturer in Marine Environmental Science at the Centre for Environmental and Marine Sciences (CEMS), University of Hull. This unit specialises in field based science has 8 full time academics, about 150 undergraduate students and 12 postgraduates. It currently has research income of around £1 million from a variety of sources including the EU, NERC, Leverhulme and from consultancy work.

I was appointed to the NEIFCA because I have a research background in crustacean biology and ecology and a long-standing voluntary relationship with the Holderness Coast Fishing Industry. Over the last 10 years I have supervised 4 postgraduate students who have worked closely with the industry to better understand their social relationships, the biology of their target species and the interactions between fishers and offshore developers. I have also worked with local fishers to better understand the impacts of fishing on the animals and to gauge population fecundity. I and the HFIG CEO, Mike Cohen, have encouraged the industry to look to the future and to put compensation from the offshore renewable industry towards future proofing themselves against new pressures on their grounds. To that end they have purchased a research vessel (the Huntress) and are looking to establish a lobster hatchery. As a scientist I look for evidence-based approaches to conservation and management and personally I care deeply about coastal fishing communities and the industry. Eventually, I would like to see fishing communities put in charge of managing their own resources inside a sensible legislative framework.

Key points

• Given the lack of adequate evidence in support of most sites, even those that have made it as far as designation in the first round (Brown et al. 2013), I welcome the caution with which the current government has approached this matter and their emphasis on socio-economic factors.

• There is very little evidence to support the use of protected areas on temperate soft sediment fishing grounds for (Bloomfield et al. 2012, Caveen et al. 2012, Coleman et al. 2013).

• The fishing industry has struggled to adequately represent itself in the face of a barrage of slick PR and misinformation from celebrity activists and well-funded and idealistically driven NGOs. Together with the incoherent and devolved approach to the development of the MCZ network (Brown et al. 2013, Oliver 2013) this has resulted in a skewed picture of the industry and the efficacy of MCZs.

• I think that the estimated £8 million spent on the consultation process has unfortunately not resulted in a science or evidence-based set of proposals for the development of MCZs. It has resulted in a rather nebulous cloud of information.

“Much of current conservation practice is based upon anecdote and myth rather than upon the systematic appraisal of the evidence . . .” (Sutherland et al. 2004)

• The economic impact data are vague and not evidenced. Some of it I just do not believe, e.g. the suggestion that the impact of the Swallow Sands site on fishers will amount to a mere £9000.

• There is a lack of detail with regards to what each of the proposed MCZs will actually mean in terms of restrictions or conservation objectives. Before implementation each MCZ should have a clear purpose and it should be clear to stakeholders with an economic interest exactly what that could mean for them in terms of restricting their activities.

“ . . it is apparent that much of their [studies of MPAs] raison d’être is advocacy for the establishment of marine reserves rather than real attempts to contribute to the science of the field” (Willis et al. 2003)

• For the Holderness Coast Inshore area I note that there is a novel suggestion that undisturbed benthic sediments are good for combating pollution. There is no evidence given to support this statement.

• In the Holderness Coast area the renewable sector carves obvious chunks out of MCZs (Figure 1). Each windfarm is in effect an exclusion zone where fishing boats will not be able to work because they will not have insurance cover and because, in the event of an incident, air-sea rescue will not be able to work inside turbine areas. Far more sensible would be to compromise and co-locate MCZs and windfarms, thus reducing the impacts of displacement on the fishing community and “unprotected” areas.

• There is a suggestion that there is a need to consider the impact of surrounding areas on MCZs and that there may need to be ancillary action/legislation in non-MCZ areas. However there is no recognition of the potentially negative impacts that designation of MCZs will have on the rest of the environment. If there are restrictions on activities in MCZs, fishermen and developers will likely concentrate their activities elsewhere which will lead to conflict and overexploitation. Rather than a broad footstep, lightly trod, with appropriate measures for each area and fishery, we could end up with unfished and heavily fished areas. This will lead to issues over comparable assessment of MCZs v other areas (Field et al. 2006).

[With the establishment of large reserves ] “considerable increases in fishing effort will be required to catch the same volume of fish, and the larger the reserves, the larger the increases will have to be” (Parrish 1999)

• Trenching activities for pipelines, aggregate extraction, gas cavern development and windfarm surveys and construction have already impacted on traditional fishing grounds in the North Eastern area. The view appears to be that MCZs are not likely to be problematic because the oceans are endless and fishermen can always move somewhere else. This is not the case.

• Each of these impacts increases the discounting rates of fishermen (i.e. increases their insecurity with regard to the likely potential to continue to make a living from fishing in the future) and detracts from the likelihood of successful local management. The likely imposition of MCZs against the will of the fishing community and in an evidence vacuum adds to the perception within the industry that the fishing community continues to be marginalized and that they have no secure rights to commons that they have been exploiting for generations.

“The scientific evidence for MPAs is limited and patchy, and many normative assumptions lie below the surface in many of the so-called ‘scientific’ arguments” (Caveen et al. 2013)

• Despite the various challenges facing the industry, fishermen in the North East IFCA region remain staunchly in support of actions that will enhance the sustainability of their industry. They have supported an increase in the minimum landing size of lobsters and a ban on landing “berried hens”, they have voluntarily v-notched tens of thousands of low-value or undersized, soft, damaged or oversized lobsters so that they cannot be landed until they have moulted several times (Rodmell, unpublished manuscript). The Holderness Fishing Industry Group has recently invested in a research vessel that they will use to look at problem areas that developers and the IFCA have not investigated and explore options for diversifying the activities of the fleet. They also plan to build a lobster hatchery in Bridlington to supplement the local population, something they believe has enhanced catches in the past (Bannister et al. 1994).

• There appears to be an irrational rush towards development of further MCZs, championed mainly by NGOs (Caveen et al. 2013). In the stampede the argument has become MCZs v no MCZs rather than “how can we best maintain the ecology and economy of our seas”.

• Our fishing grounds have survived decades of exploitation and there has been a significant decrease in the numbers of inshore boats around the coast of England since the 1980’s. There is surely time to take a scientific approach to such a big change in the management of our oceans, rather than moving towards destroying an industry because there is a gut feeling that one simplistic approach is the right one. There is no single approach to fisheries management that works in all situations – there is no panacea (Ostrom et al. 2007). We need to always bear that in mind – complex problems require complex solutions (Folke et al. 2012).

“When the only tool you have is a hammer, you tend to see every problem as a nail” (Beth Fulton, WFC 2012)

• The way to encourage sustainability and good governance is to develop certainty amongst the main stakeholders, the fishing communities, that they will still have access to their historic resource rights in the future. There is a need to refocus attention on the knowledge and data that fishermen and communities have (Johannes et al. 2000). Fishing communities and businesses where knowledge of their grounds equates to income will be slow to share their deep understanding of their areas when their local ecological knowledge is ignored/mistrusted and their views are taken as secondary in importance to those of a celebrity cook and well-meaning but misguided NGOs.

References

Bannister RCA, Addison JT, Lovewell SRJ (1994) Growth, movement, recapture rate and survival of hatchery reared lobsters (Homarus gammarus (Linnaeus, 1758)) released into the wild on the English east coast (EJ Brill, Ed.). Crustaceana 67:156–172

Bloomfield HJ, Sweeting CJ, Mill AC, Stead SM, Polunin NVC (2012) No-trawl area impacts: perceptions, compliance and fish abundances. Environmental Conservation 39:237–247

Brown C, Hull S, Frost N, Miller F (2013) In-depth review of evidence supporting the recommended Marine Conservation Zones Project Report Version ( Final Report ) March 2013.

Caveen AJ, Gray TS, Stead SM, Polunin NVC (2013) MPA policy: What lies behind the science? Marine Policy 37:3–10

Caveen AJ, Sweeting CJ, Willis TJ, Polunin NVC (2012) Are the scientific foundations of temperate marine reserves too warm and hard? Environmental Conservation 39:199–203

Coleman R a., Hoskin MG, Carlshausen E von, Davis CM (2013) Using a no-take zone to assess the impacts of fishing: Sessile epifauna appear insensitive to environmental disturbances from commercial potting. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 440:100–107

Field JC, Punt AE, Methot RD, Thomson CJ (2006) Does MPA mean “Major Problem for Assessments”? Considering the consequences of place based management. Fish and Fisheries 7:284–302

Folke C, Anderies JM, Gunderson L, Janssen MA (2012) An Uncommon Scholar of the Commons. Ecology and Society 17:1–3

Johannes RE, Freeman MMR, Hamilton RJ (2000) Ignore fishers’ knowledge and miss the boat. Fish and Fisheries 1:257–271

Oliver T (2013) MPAC Chief Slams Poor MPAs Science. Fishing News:9

Ostrom E, Janssen MA, Anderies JM (2007) Going beyond panaceas. PNAS 104:15176–15178

Parrish R (1999) Marine reserves for fisheries management: why not. California Cooperative Oceanic and Fisheries Investigations 40:77–86

Sutherland WJ, Pullin AS, Dolman PM, Knight TM (2004) The need for evidence based conservation. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 19:305–308

Willis TJ, Millar RB, Babcock RC, Tolimieri N (2003) Burdens of evidence and the benefits of marine reserves: putting Descartes before des horse? Environmental Conservation 30:97–103